Mathematics: Derivatives and integrals.

This tutorial is a general overview of derivatives and integrals (differentiation and integration). It focuses on integrals and integration, derivatives being just mentioned as an introduction of the subject. It is supposed that the reader has an intermediate knowledge of mathematics, in particular knows what mathematical functions are, and how they are graphically plotted in a Cartesian coordinate system. They are also supposed to have some knowledge of analytic geometry, understanding lines and their equations, as well as tangents to a curve. For the rest, I hope that this article is simple and clear enough to be understood by people, who don't have a calculus-level math education.

Derivatives and differentiation.

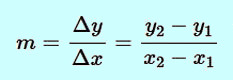

From basic analytic geometry we know that the average rate of change, also called slope, of a line y = mx + p refers to the ratio of the vertical change in y over the horizontal change in x between any two points on the line. For a line passing through to points P(x1, y1) and Q(x2, y2) the slope is given by:

|

The slope indicates the direction in which a line slants as well as its steepness. It is sometimes described as "rise over run". If the slope is positive, the line slants upward to the right. If the slope is negative, the line slants downward to the right. As the slope increases, the line becomes steeper. Examples, with slopes m=−3, m=2, and m=1/3, are shown below.

|

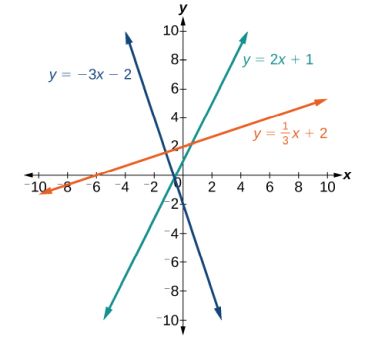

We can extend the concept of average rate of change to an arbitrary curve, by considering a secant line that cuts the curve y = f(x) through two points P and Q, defining the average rate of change over the interval [x1, x2] as the slope of this line. Giving the change in x as Δx (x2 = x1 + Δx), the two points are given as P(x, f(x)) and Q(x+Δx, f(x+Δx)), and the formula for the average rate of change may be written as:

|

Note: The expression at the right side of the equal sign in the formula above is also referred to as difference quotient.

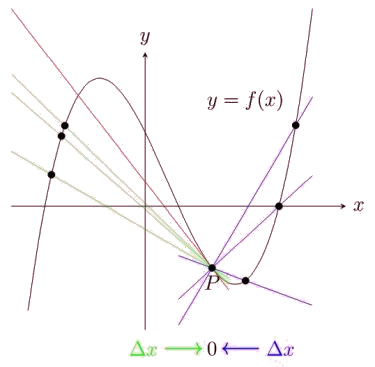

The figure below shows the secant line passing through two points P and Q of some curve f(x). The slope of this line is the average rate of change of f over the interval [x, x+Δx].

|

If we make Δx smaller and smaller, the secant line gets closer and closer to the tangent line to f(x) at the point P.

|

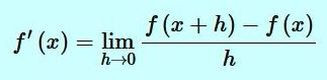

The slope of the tangent line at a given point P is referred to as instantaneous rate of change of f(x) at P. Mathematically the slope of the tangent at any point of f(x) is defined by the formula:

|

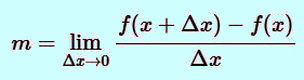

If now, instead of considering a given point, we consider the entire curve, we get a new curve, actually defined by the slopes of the tangents. This new function, denoted f'(x) [read as "f prime of x"], derived from the original function f(x), is called the derivative of f(x) with respect to x. Its official mathematical definition is as follows:

|

Notes:

- The process to find the derivative of a function is called differentiation.

- Besides f'(x), common notations for the derivative of f(x) with respect to x are: df/dx, and with y = f(x), dy/dx.

- Important to note that the derivative is only defined, if the limit at the right side of the equal sign in the formula above does exist!

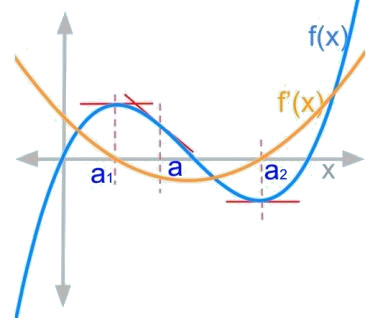

The figure below shows some relationships between the function f(x) and its derivative f'(x):

- For the maxima and minima of f(x), f'(x) is zero.

- At the maxima of f(x), f'(x) crosses 0 from positive rate of change to negative rate of change.

- At the minima of f(x), f'(x) crosses 0 from negative rate of change to positive rate of change.

|

Calculation of a derivative.

At the beginning of this tutorial, we saw a formula to calculate the average rate of change of a function over a given interval. This formula is useless to calculate the instantaneous rate of change, as this one refers to the slope of the tangent and, by definition, the tangent cuts the curve at a point P but not at any other points nearby. The slope of the tangent line at a point P(x, f(x)) on the curve of a function y = f(x) may be estimated by forming the difference quotient and figuring out what happens when Δx gets very close to 0, i.e. by calculating the limit of the difference quotient for Δx → 0. The calculation of limits is a mixture of experience and imagination, I would say. In fact, the way to proceed consists in transforming the difference quotient to an expression, that allows to preview what happens if Δx gets very close to 0.

As the primary subject of this tutorial is integration, I will not further describe such calculations. Just an example. Consider the function y = f(x) = √(625−x2) and lets compute the slope of the tangent at x = 7. The difference quotient [√(625−(7+Δx)2) − 24] / Δx may be transformed to the expression [−14 − Δx] / [√(625−(7+Δx)2) + 24]. Considering Δx = 0, we get an approximation of the slope of the tangent equal to -14 / 48 = -7/24 (in this case the slope is effectively exactly −7/24). Replacing 7 by x, transformations give us a difference quotient of [−2x − Δx] / [√(625−(x+Δx)2) + √(625−x2)]. And considering Δx = 0, we get f'(x) = -x / √(625−x2). For details concerning the transformations done, please, have a look at the article The Rate of Change of a Function at sfu.ca/math-coursenotes (to note, that this part of the tutorial is based on that article, and that most of the figures of this tutorial are extracted from that article's webpage). For further information about derivatives and their applications in practical life, the article The Derivative Function at sfu.ca/math-coursenotes may be useful.

To do calculations involving derivatives, knowing the derivatives of common functions is a precious help. Here are some examples (you find more of them in the Differentiation and Integration article at CueMath).

| f(x) = K | f'(x) = 0 |

| f(x) = xn | f'(x) = nxn-1 |

| f(x) = ln(x) | f'(x) = 1/x |

| f(x) = ex | f'(x) = ex |

| f(x) = sin(x) | f'(x) = cos(x) |

| f(x) = cos(x) | f'(x) = -sin(x) |

Integrals and integration.

There are three reasons why I started the tutorial (mostly about integration) with talking about derivatives. First, the tutorial is a good place to introduce this important concept to people who haven't studied the calculus. Second, differentiation is generally considered as easier than integration; thus speaking about derivatives may make it easier to understand integrals. Third, and this is the main reason: Integrals and derivatives are directly related.

Lets start with the following definition: A function F is an antiderivative of f on a given interval, if F′(x) = f(x) for all x in this interval. Example: The function F(x) = x2 is an antiderivative of f(x)= 2x, because (cf. formulas above) the derivative of F(x), F'(X) = 2·x2-1 = 2x. However, as the derivative of a constant is zero, the derivative of G(x) = x2 + 1 is also 2x, as is the derivative of H(x) = x2 - 1, etc. With other words, if a function F is an antiderivative of f on a given interval, then the general antiderivative of f on this interval is F(x) + C, where C is any real constant.

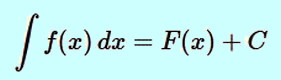

Now we can define the indefinite integral of a real-valued function f(x) with respect to a real variable x: It is the set of all antiderivatives of the function f(x). This integral is denoted by ∫f(x)dx, and is read as "the integral of f with respect to x"). Mathematically, it can be formulated as follows:

|

where F'(x) = f(x), and C is any real constant.

Thus, the indefinite integral is a function (more precisely, a set of functions). Integrating f(x) means finding the integral of f(x); this process is also called integration.

Note: In the formula above, ∫ is called the integral sign, the function f is referred to as the integrand of the integral, the variable x is called the variable of integration, and dx is called differential.

Some important properties of integrals:

- The integral of the derivative of a function f(x) is equal to f(x): ∫f′(x)dx = f(x).

- The integral of a function f(x) multiplied by a constant k is equal to k times the integral of f(x), i.e. we can factor multiplicative constants out of an integral: ∫kf(x)dx = k∫f(x). In particular: ∫−f(x)dx = −∫f(x)dx.

- The integral of a sum or difference of two functions f(x) and g(x) is equal to the sum resp. difference of the integrals of f(x) and g(x): ∫f(x)±g(x)dx = ∫f(x)dx±∫g(x)dx.

Important note: The property for sums/differences of two functions does not apply to the product or quotient of two functions!

Simple calculation example: What is ∫sin(x)dx? We know from the common derivatives table above that cos'(x) = -sin(x). So ∫cos'(x) = cos(x) + C, ∫-sin(x) = cos(x) + C. Factoring out the -1 multiplier constant, we get -∫sin(x) = cos(x) + C, so ∫sin(x) = -cos(x) + C.

Here is a practical ("real world") example of indefinite integral calculation. Consider a linear movement in one dimension characterized by a variable velocity v due to a

constant acceleration a. As a is a constant, the velocity a time t is given by vt = v0 + at, where v0 is the velocity at time t = 0. How

can we find the displacement s at a given time t?

Velocity is the variation of the displacement versus time, i.e. v = ds/dt. If v is the derivative of s with respect to t, then s is the integral of v with respect to t:

s = ∫vdt = ∫(v0 + at)dt. The calculation of this integral yields s = v0t + ½at2 + C. The constant C being nothing else than the

displacement at time t = 0, we get the well known formula: s = s0 + v0t + ½at2.

Definite integrals.

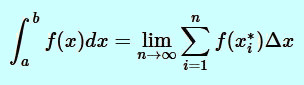

The definition of a definite integral is mathematically formulated as follows: If f(x) is a function defined on an interval [a,b], the definite integral of f from a to b is given by

|

provided that the limit exists (otherwise the function cannot be integrated on [a,b]).

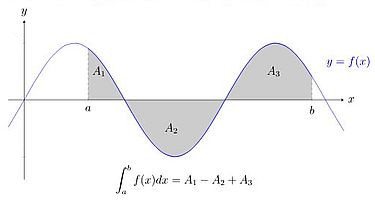

What this is about must not really bother you. The important point is that whereas the indefinite integral is a function, the definite integral is a number. A number with a very precise and "practical life" meaning: The definite integral of a function f from a to b represents the area of the region between the graph of f and the x-axis, for the interval [a,b] (i.e. for x belonging to [a,b]).

Important note: The area below the graph (area above the x-axis) is considered as positive, the area above the graph (area below the x-axis) is considered as negative. The net area (the value of the definite integral) is the sum of the different positive and negative areas.

|

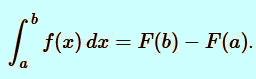

The formula to calculate a definite integral is often referred to as the fundamental theorem of Calculus. It can be formulated as follows: If f(x) is a function, that is continuous on the interval [a,b], and if F(x) is any antiderivative of f(x), then

|

In other words, to calculate the definite integral of a function f(x) over the interval [a,b] we have to find a function F(x), with the property F′(x) = f(x), and then compute F(b) − F(a).

Example: Calculate the definite integral A of the function f(x) = 2x - 4 for the interval [-3, 2].

Antiderivatives of f(x) are x2 - 4x + C. Thus, A = [22 - 4*2 + C] - [(-3)2 - 4*(-3) + C] = (4 - 8) - (9 + 12) = -4 - 21 = -25.

The figure below shows the graph of the function (in blue) and the integral area for the interval considered (in cyan).

![Definite integral as area example [1] Definite integral as area example [1]](../pics/area2.jpg) |

The figure shows us that the area is in fact a right triangle, so we can easily calculate it and check if our integral calculation is exact.

Triangle area = [2 - (-3)] * [0 - (-10)] / 2 = (5 * 10) / 2 = 50 / 2 = 25. As it is entirely located above the graph, it is equal to the integral net area, but this

last one is considered being negative (-25, as calculated above).

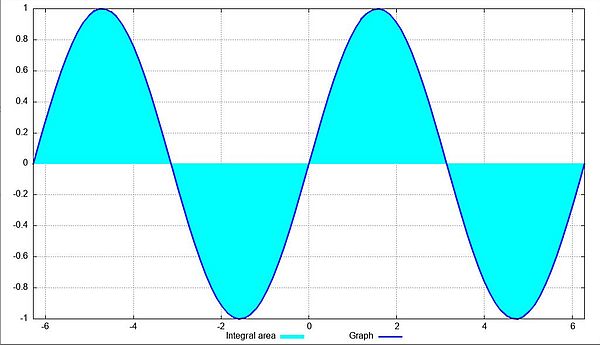

Other example: Calculate the definite integral A of the function f(x) = sin(x) for the interval [-2π, 2π].

Antiderivatives of sin(x) are -cos(x) + C. Thus, A = -cos(2π) - [-cos(-2π)] = -1 - (-1) = 0.

The figure below shows the graph of the sine function (in blue) and the integral area for the interval considered (in cyan).

![Definite integral as area example [2] Definite integral as area example [2]](../pics/area3.jpg) |

Without doing any calculations, we can see that the area below the graph equals the area above the graph, thus the net area, i.e. the value of the definite interval is 0.

Calculation of an integral.

Knowing the integrals of common functions is a precious help. Here some examples (you find more of them in the Differentiation and Integration article at CueMath).

| f(x) = K | ∫f(x)dx = Kx + C |

| f(x) = xn (n ≠ -1) | ∫f(x)dx = xn+1/(n + 1) + C |

| f(x) = 1/x | ∫f(x)dx = ln(x) + C |

| f(x) = ex | ∫f(x)dx = ex + C |

| f(x) = sin(x) | ∫f(x)dx = -cos(x) + C |

| f(x) = cos(x) | ∫f(x)dx = sin(x) + C |

Also important to know the rule concerning the integral of a function multiplied by a constant and the rule concerning the integral of the sum/difference of two functions, mentioned earlier in the tutorial.

Furthermore, there are several so-called methods of integration:

- Decomposition method

- Integration by Substitution

- Integration using Partial Fractions

- Integration by Parts

You can find a description of these methods, together with examples, in the Integration article at CueMath.

Numerical integration.

Methods of integration allow to calculate (i.e. determining the exact value) of lots of definite integrals. However, for lots of functions it is either not possible or really hard to apply these methods. In this case, we use numerical integration (sometimes called quadrature), that is the approximate computation of an integral using numerical techniques.

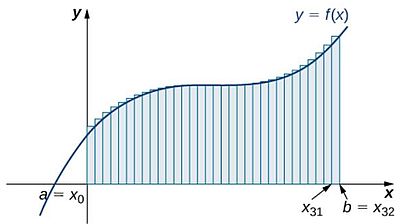

We have said above that the definite integral of a function f from a to b represents the area of the region between the graph of f and the x-axis, for the interval [a,b]. Numerical integration consists in dividing the area region into many small shapes that have known area formulas; summing these areas, we obtain a reasonable estimate of the true area, the accuracy of our calculation increasing with the number of shapes (also called partitions).

So, we divide the interval [a,b] into n subintervals of equal width (b−a)/n. This is done by selecting equally spaced points x0, x1, x2,

…, xn with x0 = a and xn = b. The relationship between two (x values of) successive points is thus given by:

xi − xi−1 = (b−a)/n (for i=1,2,3,…,n)

or, with setting Δx = (b−a)/n

xi = x0 + iΔx (for i=1,2,3,…,n).

The most obvious shape to use is the rectangle. On the figure below, the area region is divided into 32 equal subintervals. Calculating the sum of the areas of the 32 rectangles gives an approximation of the value of the integral for the interval [a,b].

|

You can see on the figure that for the interval [xi-1, xi], we chose f(xi) as function value. This is called right rectangular approximation method (RRAM) (or right-endpoint approximation). An alternative is to choose f(xi-1) as function value; this is then called left rectangular approximation method (LRAM) (or left-endpoint approximation). Finally, we can take the function value of a point located at the center of an interval (i.e. at equal distance from the two endpoints); this is called midpoint rectangular approximation method (MRAM) (or midpoint approximation).

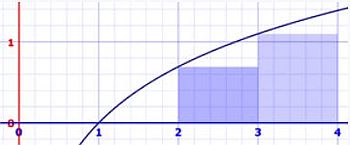

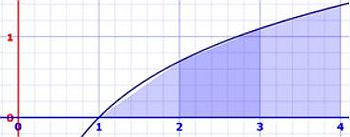

Lets consider a simple example (taken from the Math Is Fun website: Calculation of ∫ln(x)dx for the interval [1,4]. For simplicity, lets consider 3 partitions, thus Δx = (4−1)/3 = 1 and our x values are respectively 1, 2, 3, and 4.

In this case we would not really need to use numerical integration, as the integral can be calculated. The formula is ∫ln(x)dx = xln(x) - x + C, and the exact value for the interval [1,4] is 2.54517744447956…

Using LRAM, we get:

- [1,2]: 1 * ln(1) = 0

- [2,3]: 1 * ln(2) = 0.693147

- [3,4]: 1 * ln(3) = 1.098612

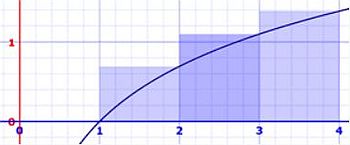

Now lets use RRAM:

- [1,2]: 1 * ln(2) = 0.693147

- [2,3]: 1 * ln(3) = 1.098612

- [3,4]: 1 * ln(4) = 1.386294

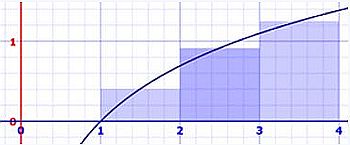

Finally, lets use MRAM:

- [1,2]: 1 * ln(1.5) = 0.405465

- [2,3]: 1 * ln(2.5) = 0.916291

- [3,4]: 1 * ln(3.5) = 1.252763

The figures below show the areas used to do the calculations. The "not filled area" on the left screenshot explains why the value calculated using the LRAM method is lots too small. The "too much filled area" on the middle screenshot explains why the value calculated using the RRAM method is lots too big. On the screenshot on the right, we can see that using the MRAM method the "not filled area" and the "too much filled area" "neutralize each other", thus we get a rather accurate result.

|

|

|

The three calculation methods (that are in fact special cases of the so-called Riemann sums, where xi can be any point of the subinterval) can be put into formulas.

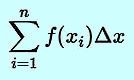

Riemann sum: Left hand rule summation.

|

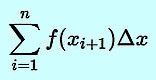

Riemann sum: Right hand rule summation.

|

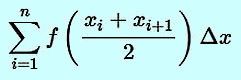

Riemann sum: Midpoint rule summation.

|

Instead of using shapes with a horizontal top (rectangles), we can also use shapes with a sloped top (trapezoids, or possibly triangles). The picture shows the trapezoidal method areas for the integral of our example above.

|

Lets do the calculation:

- [1,2]: 1 * [ln(1) + ln(2)]/2 = 0.346573

- [2,3]: 1 * [ln(2) + ln(3)]/2 = 0.895879

- [3,4]: 1 * [ln(3) + ln(4)]/2 = 1.242453

In this example, Δxk = Δx is the same for all intervals. This is not mandatory. The general formula (variable Δxk) is the following:

![Formula: Trapezoidal rule summation [1] Formula: Trapezoidal rule summation [1]](../pics/trapezoidal1.jpg) |

If Δx is the same for all intervals, each value gets used twice, except for the first and the last, and then the whole sum is divided by 2. We get the (simpler, from the point of view calculations to do) formula:

![Formula: Trapezoidal rule summation [2] Formula: Trapezoidal rule summation [2]](../pics/trapezoidal2.jpg) |

To get an analogy with the formula of Simpson's rule (cf. below), we can rewrite this latter formula as follows:

![Formula: Trapezoidal rule summation [3] Formula: Trapezoidal rule summation [3]](../pics/trapezoidal3.jpg) |

Note: The trapezoidal method is in fact nothing more than the average of LRAM and RRAM.

It is obvious that the accuracy of the approximation depends on the function (shape of the curve). Also, the accuracy increases when increasing the number of subintervals. Using a computer program, approximations with a high number of subintervals may be done without problem. However, when doing so, it's normally none of the methods described that are used. In fact, there are more complicate methods, normally yielding better results (lower error values). The probably most often used method is Simpson's Rule, that is in fact an improvement of the trapezoidal rule.

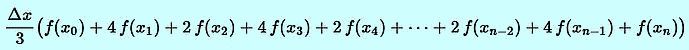

Instead of the sloped top used with the trapezoidal rule, Simpson's rule uses parabolas. In many cases, the parabolas get quite close to the real curve and thus this approximation method generally has a good accuracy. Using parabolas sounds complicated, but the formula that we end up with is relatively simple (note, that with Simpson's rule the number of subintervals must be pair!):

|

In the best possible case, the approximated value equals the effective value of the interval. In the worst case, there is a maximum error of approximation. This maximum error may be calculated for each of the approximation methods described. For details (formulas, plus examples), cf. the Math Is Fun website.

Simpson's rule generally has a good accuracy ... provided that we choose the number of subintervals high enough. It is obvious that this kind of calculation would take lots of efforts to do by hand. Thus, approximation of an integral area using Simpson's rule is primarily used in computer programs. But even in this case, it may not be the best solution. Consider, for example, a function that is slowly varying for x > 0 and rapidly varying for x < 0. In such a case, we are faced with a dilemma:

- Choosing n large for accurate approximation when x < 0 but performing a wasteful computation for x > 0.

- Choosing a smaller n for economical computation when x > 0, but getting a large error for x < 0.

Conclusion: To perform an accurate approximation of an interval area without wasting computer resources, we need a method which can adjust the value of Δx to the amount of variation in the integrand. This may be achieved by using the Adaptive Simpson method that we can describe as follows:

| Adaptive Simpson method uses an estimate of the error we get from calculating a definite integral using Simpson's rule. If the error exceeds a user-specified tolerance, the algorithm calls for subdividing the interval of integration in two and applying adaptive Simpson's method to each subinterval in a recursive manner. |

There are lots of Internet articles about the Adaptive Simpson method and possible algorithms to implement it in a computer program. Here is the link to one of them (including code samples in BASIC and C): Adaptive Simpson and Romberg integration methods on the HP Forums website.

Note: There are several other integral approximation methods. The Romberg method is explained in the article mentioned above. More modern methods are the Gauss–Kronrod quadrature, and the Clenshaw–Curtis quadrature.

My Free Pascal "Integration" unit.

I have written a simple integration related unit using Free Pascal. The unit includes 2 functions:

- Integrate(): Numerical integration using the Adaptive Simpson's method of a mathematical function passed as parameter. The Integrate() function has 3 mandatory and 2 optional parameters: the mathematical function of type TFunction = function(X: Real): Real; the 2 interval values of type Real; the tolerance desired (default = 1E-9), and the depth (default = 1000). To note that the code of this function is in fact a re-write of of the code published at the Rosetta Code website.

- IntegralArea(): Plot of the graph with the integral area of a function passed as parameter. The IntegralArea() function has 3 mandatory and 1 optional parameters: the mathematical function of type string: the 2 interval values of type Real; the filename of the plot (default = 'plot'). In fact, the function generates a .plt file that it passes to the freeware program gnuplot, that creates a PNG image file of the plot.

Here is the code of my "Integration" unit. You can download the source code of the unit, together with two simple Lazarus command line projects, that show how to use the functions of the unit.

unit Integration;

interface

type

TFunction = function(X: Real): Real;

function Integrate(F: TFunction; A, B: Real; Tol: Real = 1E-9; Depth: Integer = 1000): Real;

function IntegralArea(SF: string; A, B: Real; FN: string = 'plot'): Boolean;

implementation

uses

SysUtils, Process;

var

FA, FB, M, FM, Whole: Real;

{ Numerical integration using the Adaptive Simpson's method (Lyness, 1969) }

function Integrate(F: TFunction; A, B: Real; Tol: Real = 1E-9; Depth: Integer = 1000): Real;

// This is a re-write of the code published at the "Rosetta Code" website

// (https://rosettacode.org/wiki/Numerical_integration/Adaptive_Simpson%27s_method#Pascal)

procedure Integrate_Simpsons_(A, FA, B, FB: Real; var M, FM, Quadval: Real);

begin

M := (A + B) / 2;

FM := F(M);

Quadval := ((B - A) / 6) * (FA + (4 * FM) + FB);

end;

function Integrate_(A, FA, B, FB, Tol, Whole, M, FM: Real; Depth: Integer): Real;

var

LM, FLM, Left, RM, FRM, Right, Delta, Tol_, Int: Real;

begin

Integrate_Simpsons_(A, FA, M, FM, LM, FLM, Left);

Integrate_simpsons_(M, FM, B, FB, RM, FRM, Right);

Delta := Left + Right - Whole;

Tol_ := Tol / 2;

if (Depth <= 0) or (Tol_ = Tol) or (Abs(Delta) <= 15 * Tol) then

Int := Left + Right + (Delta / 15)

else

Int := (Integrate_(A, FA, M, FM, Tol_, Left, LM, FLM, Depth - 1) + Integrate_(M, FM, B, FB, Tol_, Right, RM, FRM, Depth - 1));

Result := Int;

end;

begin

FA := F(A);

FB := F(B);

Integrate_simpsons_(A, FA, B, FB, M, FM, Whole);

Result := Integrate_(A, FA, B, FB, Tol, Whole, M, FM, Depth)

end;

{ Plot of the graph with the integral area }

function IntegralArea(SF: string; A, B: Real; FN: string = 'plot'): Boolean;

// The plot is done by calling Gnuplot

var

S: string;

OK: Boolean;

OutFile: Text;

begin

OK := True;

FN += '.png';

Assign(OutFile, 'plot.plt'); Rewrite(OutFile);

Writeln(OutFile, 'set terminal png size 1080,620');

Writeln(OutFile, 'set output "', FN, '"');

Writeln(OutFile, 'set grid');

Writeln(OutFile, 'set key horizontal outside center bottom');

Writeln(OutFile, 'plot [', FloatToStr(A), ':', FloatToStr(B), '] ',

SF, ' w filledc y1=0 lc "cyan" t "Integral area",',

SF, ' w lines lc "blue" lw 3 t "Graph"');

Close(OutFile);

if FileExists(FN) then

DeleteFile(FN);

OK := RunCommand('gnuplot', ['plot.plt'], S);

Result := OK;

end;

end.

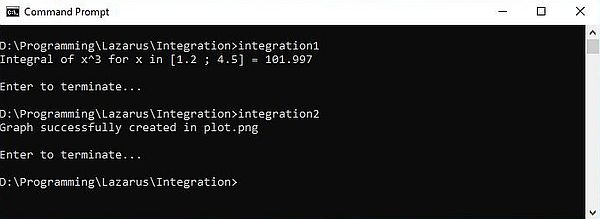

The screenshot below shows the execution of the demo programs "integration1" and "integration2" included in the "Integration" download archive.

|

And here is the screenshot of the plot of the sine function and the integral area of this function for the interval [-2π ; 2π] generated by gnuplot.

|

If you find this tutorial helpful, please, support me and this website by signing my guestbook.